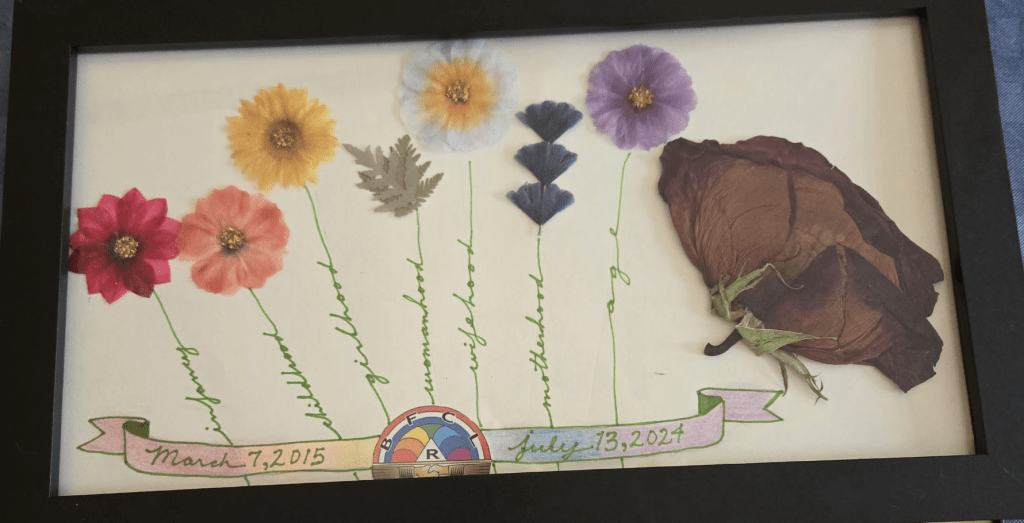

I just got home from a very refreshing trip to Minnesota to meet up with a cousin and swap genealogy treasures and stories. 10 out of 10, highly recommend! Our particular ancestry is rooted in the Volga German migration from Russia in the 1870s to the American plains of rural Kansas. During our visit, my cousin asked what our ancestors would have burned to stay warm since Kansas is known for its severe lack of forests. My quick answer was “cow chips”, as it is documented that pioneers on the Great Plains resorted to burning dried cow and bison manure due to the absence of trees.

But then on my 8 hour drive home, I got to thinking–perhaps I should have elaborated. It dawned on me that my cousin has always grown up in the very urban (by northwest Kansas standards) region of Wisconsin and Minnesota, far removed from where our ancestors put down roots in 1875-1876. On the other side of the coin, I grew up ONLY in northwest Kansas and was fully immersed in the mindsets and habits of our migratory relatives. It was a bit of a lightbulb moment for me–and my cousin had predicted I would probably have some of those. Not sure pioneer heating practices is what he thought was going to trip my trigger, but here we are.

Here’s the deal–I tend to be a bit defensive when Easterners make references to how primitive Kansas is. I once had some cousins (different family branch, NOT Volga German) from New York come out to visit. They spent hours with their eyes as big as saucers and acting quite skittish–when I asked what was weighing on them, they asked if it was scary to ride to the town an hour away for groceries on horses and buggies when the Indians could attack at any moment.

Yes, they were dead serious. Yes, I laughed at their expense. And then I assured them that we had cars and trucks and running water and all that modern stuff. They never were fully convinced, and I found out over the years that they weren’t the only people from the east who had this misconception. It was irritating, and I got in the habit of not giving people a chance to think we were all still living in the Wild West out here.

But my cousin was not being condescending about it; he truly was curious and wanted to know how our ancestors survived the harsh winters when they arrived. So for once I am going to drop my defenses and admit (begrudgingly) that we did grow up using some of the old tricks our ancestors used. For Steve, I will put out my theories based on knowing how our relatives lived even in the 1900s.

First, we need to think about the Volga Germans. These people came over to Kansas after a hundred-year stint in the very arctic climate of Russia–that’s not for the weak, folks! Steve commented that his dad really disliked heat, and I can confirm that my dad, too, did not like heat. I also love me some air conditioning. At a genetic level, I think some of our ancestors were coded to prefer a cooler climate. And as a lifelong Kansas resident, I can say that we don’t always have a consistently frigid winter. Yes, it can get quite cold and drop to -22 degrees Fahrenheit, but it doesn’t last forever and ever. And that is a key consideration–do you know how stubborn your average Volga German can be? We can outlast anything through sheer spite for quite some time. It is the middle of November right now, and it was almost 70 degrees today–yes, that is somewhat unusual even for us, but Kansas weather is very unpredictable. I will say that our “cold” season is from November to the end of February/early March, but by “cold” I mean the temperatures hover in the 30s and 40s most of that time, dropping into the single digits or negative temperatures for a few weeks in January and February. Now, there is always that freak season where it is frozen and blasting an arctic wind for weeks on end and you would cuss about it if it didn’t mean exposing your airways to the cold. But we are just as likely to get a freak day in mid-January in the mid-80s and everyone breaks out the shorts. I would hazard to guess there were years that they worried we wouldn’t get a long enough freeze to allow them to harvest the thick ice blocks from Big Creek to provide refrigeration in the summer.

Speaking of clothing, let’s go over that. You know how wearing dark colors in the summer can make you overheat? Kansas is quite sunny, and even in the dead of winter dark clothing is going to get warmed by the sun. Add to that the fact that some clothing is made of wool and worn in layers, and it can be fairly easy to dress to absorb ambient heat. Our ancestors also hunted and trapped, so they had access to furs to make coats and hats and gloves that were quite toasty. Cartoons make fun of union suits, but men and women both sported them under their clothes in the winter. Layers keep you warm.

Moving on to lodging considerations, most of the Volga German homes were made of limestone initially. I’m not going to say that there were NO trees in the area for several reasons. First, people in Kansas had tree claim homesteads, which meant that they had to plant trees on their property to improve it when they bought it; they generally brought their little seeds and saplings along with them when they arrived so they could plant them right away and work on keeping them alive. So after a few years and a lot of water hauling, there were tree groves popping up. Second, we all know a bear shits in the woods–but we also have to realize that birds migrating from the north do their fair share of defecating. We have all seen a random tree growing up along a fence line because some bird ate seeds and then sat on the fence wire and deposited those seeds with a healthy dose of fertilizer. It stands to reason that all of the migratory birds were also “planting” trees in their travels over the grassy plains of Kansas.

So there were trees, but there were not a lot of them. And here come the Volga Germans, practical as can be. When they take stock of their resources and see a few trees and a whole bluff of limestone, do you really think they are going to waste their fuel source on a house? I can just hear my ancestors now, looking out of their foot-thick (think insulating qualities here) limestone home at some English neighbor in their wooden home and scoffing, “Look at dat dere dummkopf freezing in dat pile a kindling since dey jus’ hat ta haf dat vooden haus. Bah!”

Our ancestors were quite resourceful, so when they ran out of what little wood was growing around their area, they most likely found other stuff to burn before they resorted to cow chips. We know they rendered beef tallow and lard, and those burn and can put off heat, and we know they bought kerosene and oil. They grew crops, and corn husks and cobs and grain stalks could be burned. For that matter, grass could also be burned even if it didn’t last long like a log. And our ancestors burned their garbage. I grew up with a burn barrel on our farm, and I know our ancestors burned even more trash than we did. Broken tools, furniture, food scraps, anything and everything went into the stove when it could no longer be used, patched, and repaired. The wind and rain were also not kind to abandoned buildings, so if the neighbors gave up and headed back east, our ancestors would have put that dilapidated structure to good use if the weather blew it down. And if the weather needed a little help, they could nudge it.

Our relatives also worked and lived near the railroad. The trains ran on coal, and coal fell out of the coal car as it chugged down the tracks. The kids walking home from school and following the tracks would have been sure to collect any chunks of coal they found lying by the tracks, along with any stray seeds and grain that their families could plant for crops. The tracks were made of creosote-coated logs, and when the railway workers replaced them as they wore out, the locals would haul them away. I grew up seeing many railroad ties used as boundary lines and planting boxes, but they also could be used as firewood. Creosote stinks, but it burns–we can put up with stench if it means not freezing to death.

Daily life was also a little different back then. Now family members all scatter throughout a home, but back then in the winter they stuck to the room with the woodburning stove in it. I grew up in a turn of the century farm house that was heated by a woodburning stove in the living room and a forced air furnace in the basement. I didn’t experience central air and heat until I went to college–heaven! There was no heat source upstairs where our bedrooms were. During the day, we all clustered in the living room where it was warm (that’s also where the furnace vent was along with the stove). At bedtime, our beds were covered with 5 or more blankets and quilts; we shivered and chattered until our body heat warmed up our beds under that heavy weight of all of those layers of blankets. We also dressed for bed in layers–two pairs of socks, thermal underwear or union suits, and pajamas. Function over fashion, people. Back in our ancestors’ time, they also would have been sharing their beds with multiple people, and body heat is a wonderful thing in the dead of winter. They also probably had furs layered in with all of the quilts.

So yeah, that is my educated and somewhat experienced guess on how they stayed warm for a couple months until the spring thaw hit. I may be completely off-base on some of it, but for the most part I lived it and will fight you on it. I am a Volga German after all.